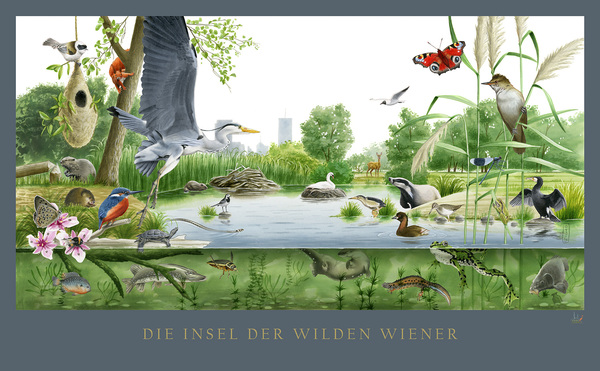

An uninhabited island in the middle of the big city, where deer and beavers live, where grey herons and cormorants find rich fishing grounds, where marsupial tits build their elaborate nests? A romantic dream?

Inner-city nature reserves or fallow land are under high investment pressure. Almost everywhere this leads to them being given over to the market and nature having to make way for office buildings, and in the best case a mix with luxury residential complexes.

An outstanding example that a city can also decide differently is offered by the municipality of Vienna with the Danube Island. The Danube Island is a long island strip in the middle of the Danube between the city centre and the expansion areas of the city in the south and the districts and expansion areas on the north side of the Danube – in other words, precious inner-city land, ideal for investors. But the city has said no and decided to preserve this area as a nature reserve. In summer, the Viennese flock there for bathing and picnics; in the less pleasant seasons, the island is only visited by walkers. A successful cohabitation between people in a large, dense city and a kind of fauna and flora that can otherwise only be found far away from the urban.

Two top-class, internationally renowned photographers have now, after years of observational work, captured this wild life on the Danube Island in a large book, in wonderful, breath-taking photographs, accompanied by interesting and vividly written texts that give an insight into these living worlds and the measures taken to preserve them. The photographers Verena Popp-Hackner and Georg Popp specialise in urban wilderness, and a few years ago published the much-praised book ‘Wiener Wildnis’: www.wienerwildnis.at – already almost out of print!

The Danube Island book is now the continuation of Viennese Wilderness on the city’s waterfronts, a portrait of the unique inner-city natural space of the Danube Island with its exciting life that goes along quite unrecognised and secretly next to that of the city dwellers. At the same time, the accompanying texts shed light on the measures that are needed to make this coexistence work. For even urban wilderness does not come for free – here, too, preserving and controlling measures are necessary. An insight into the field of urban ecology is given and understanding is awakened. How precious and valuable such inner-city natural areas are, how exemplary and sensible the decision of a city to preserve ‘urban wilderness’ is, has now been shown in the time of the Corona pandemic: The population has, with the necessary distance, an opportunity to catch their breath and go for a walk in the middle of the city.