Amsterdam 1671-1672 The ‘Golden Bay’ of the Herengracht. Painting by Gerrit Adriaensz. Berckheyde, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

On the development of Amsterdam in the 17th century as a paradigm of blue-green urban planning and on a successful example in today’s Vienna

Nothing seems more antiquated in a time of rapid change than this headline. But that would be blind to history. As the history of Europe shows, rapid changes in the framework conditions of both social and personal life were not uncommon – and a reaction to this was sometimes forward-looking planning, which was implemented with large-scale interventions and then stood the test of time for centuries. The often short term view especially in the area ofarchitecture, infrastructure and urban development. An impressive example of this is the urban development of Amsterdam.

The 17th century saw Amsterdam grow five and a half times its population within 100 years due to migration. It was a century that shook up Europe to an extent unimaginable today. Key words: the 30 Years’ War, which devastated Central Europe and probably cost the lives of almost a third of the population. In the Netherlands, this long war had already been preceded by 40 years of war in the battles for liberation. The war was preceded by the liberation of Spain and went down in history as the 80 Years’ War.

But instead of drowning in refugee misery, the city of Amsterdam has experienced an unprecedented blossoming in this century, not least because of this. This is due, among other things, to a far-sighted urban development policy that produced solutions for housing, commerce, transport and, not least, the integration of nature into the city – solutions that are, or rather should be, exemplary in parts even today.

Downright revolutionary urban planning in the 17th century

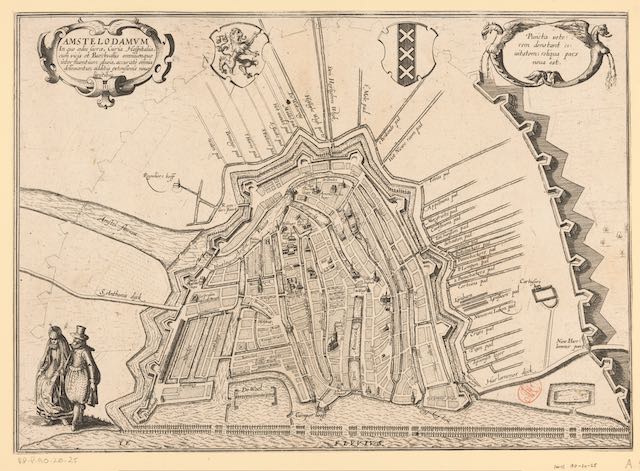

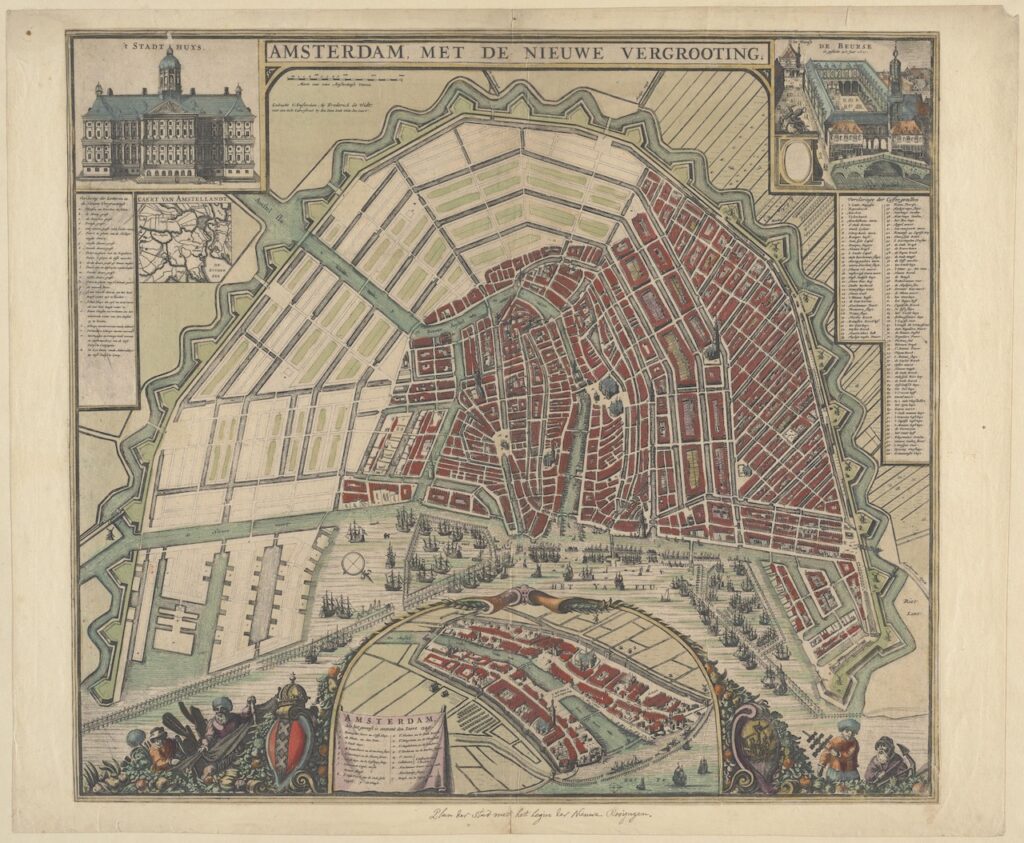

As early as 1600, people began to think about urban expansion planning. In 1612, the municipal council adopted the first part of an almost revolutionary urban development plan which, together with two other subsequent plans, structured the expansion of the city for the next few centuries – a plan that was finally adopted in 1662 and on which the city worked until the second half of the 19th century.

Around the relatively small city centre, a huge expansion area was designed into the surrounding, chaotically built-up suburban areas. Wide canals, known in Dutch as “Grachten”, were central to the drainage and sewage system. The planting of trees along the canals was standardised – elms, which to this day are a characteristic feature of Amsterdam and are among the largest stands of elms in Europe. The inner courtyards of the blocks were designed as pleasure gardens. The rainwater, on the other hand was collected in rainwater tanks as a drinking water supply.

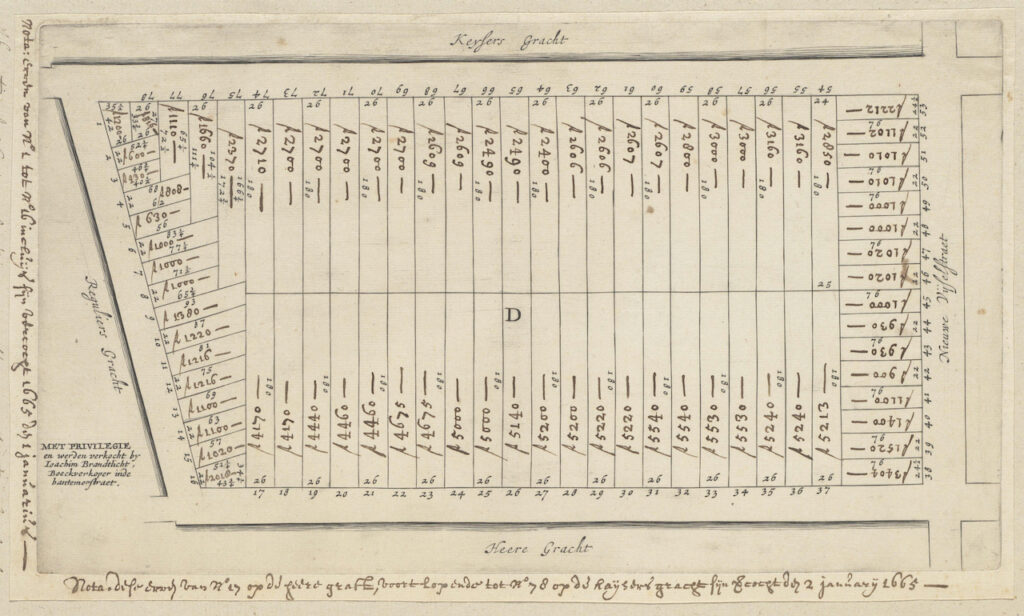

For the area along the canals, the plan stipulated a narrow parcelling out, with a uniform building width of 7.5-10 m (or double this) for the main canals and 5.5 m for the transverse canals. A uniform building depth of 30 metres was also specified for the entire area – this was to ensure that the inner zones of the building blocks remained undeveloped, with only a garden pavilion permitted. This was because the inner zones were to be preserved as landscaped pleasure gardens – green recreation right next to the house. Businesses were prohibited, although non-disturbing items such as offices were tacitly permitted. The resulting canal belt was reserved for luxurious living. The city council, sober-minded merchants, formulated three goals for this major urban expansion: functionality, urban beauty and return on investment for the city.

Outgoing invoice

The plan worked: wealthy merchants and reeves as well as wealthy refugees settled there. The immense costs were financed by the sale of the plots at top prices, including the obligation for the new owners to bear the costs of the infrastructure, i.e. to finance the construction of the canals, the paving of the streets and the planting of trees. The owners of the suburban areas into which this planning was designed were expropriated for this urban expansion and duly compensated according to (pre-planning) market value.

The decision and realisation of the plan was carried out in three major stages, starting with the first stage in the west. In 1662, the plan for the entire, characteristic semicircle around the historic town centre was approved. Even though not all the plots were sold for years – the city suffered repeated setbacks, for example due to waves of plague that dramatically decimated the population – the whole city was still able to realise its full potential: in 1600, Amsterdam was still one of the many medium-sized cities in Europe with a population of around 30,000.

In the second half of the 17th century, it had grown to become the third largest city in Europe after London and Paris and had become an urban mecca – something that Paris also achieved 200 years later with the rigorous planning of Baron Georges Eugène Haussmann, which was also questioned philosophically, for example by Walter Benjamin.

What is still instructive about this astonishing story today?

Firstly, the high density, which was also achieved through the extraordinary building depth. In most cases, a narrow inner courtyard was created in the centre of the permitted building depth, while in the approx. 14 m deep front buildings, the centrally located stairwells have a dark chamber at their rear, which was often used for the installation of sanitary cells from the 19th century onwards. The great depth of the buildings with their narrow outer sides brings considerable energy benefits: the buildings have little external surface area and to a certain extent warm each other. The lower storeys are adequately lit by high windows, which is made possible by the great storey height – even from today’s perspective, this still has a healthy effect on the indoor air. The upper floors, which receive more outside light, were designed lower.

Thanks to the open water of the canal system and the dense tree planting along the canals, the city now has a unique temperature reduction and air purification system, which is also the basis for a rich bird and insect life. An urban biotope – a Biotope City. Grey water (previously discharged into the canals) is now drained into the nearby dunes for purification. Rainwater, the former drinking water that was pumped up from the rainwater cellars, can now be channelled backwards into the gardens. The use of bricks for the entire street paving allows some of the rainwater to seep through – both important measures to feed the groundwater level during long dry summer weeks. In addition, flooding has never occurred in the canal belt during heavy, prolonged downpours.

Icon of capitalism and Europe’s most planned city

The buildings are ideally suited for mixed residential and office use, with shops and restaurants on the ground floors of the sidewalks, where people of lesser means who could not afford a bel étage used to live.

A history of urban planning by forward-thinking merchants, shipowners and factory owners, who formed the municipal council, with their experts in fortress construction (because the urban expansion had to be secured in the first instance by a fortress belt) and urban architects who have been at the cutting edge of architectural discourse since of antiquity and at the same time recognised the spirit of the times. “Amsterdam was the icon of capitalism and at the same time the most planned city in Europe,” writes the historian Jaap Evert Abrahamse, who dedicated a luminescent oeuvre to this planning1 .

Learning from the past ?

Is the city of Amsterdam learning the lessons of its own history for its current planning? Regrettably, the answer is no. When the Sluisbuurt urban expansion area was planned a few years ago, the result was a jumble of tower blocks and low-rise buildings, with no green outdoor spaces to speak of, let alone gardens. The renowned Dutch architect Sjoerd Soeters presented an alternative plan, a modern continuation of the canal belt, with lots of green open space that invites people to spend time outdoors – with the same building density as the city’s plan, but no potpourri of building heights with prominent high-rises.(2)

The Biotope City Foundation was delighted with this design and proposed an Amsterdam Biotope City on this basis, as had just been created in Vienna. It did not work. The new Sluisbuurt neighbourhood is being built according to a model that merely maximises returns for some investors using tried and tested methods, without taking into account the other two criteria of forward-looking 17th century planning: Functionality for healthy, recreational living (and, if desired, domestic or residential work), and urban beauty. One could shrug off such a plan, were it not for the misguided reality that it would entail for at least the next few decades, which buyers on the tight housing market will have to pay for – and which may then lead to a clear-cutting in a few decades’ time.

How to do it differently

Finally, the author of these lines would like to point out a modern, realised Biotope City: the Biotope City Wienerberg, ready for occupancy at the end of 2021, pilot project of the International Building Exhibition Vienna 2022, highly dense (GFZ 3.0) and at the same time with shrubs, meadows and lawns for play areas and with so many trees that, planted next to each other, they would form a forest of 2 ha.

The 5.4 ha area, formerly completely sealed by halls and car parks, but now only 40% sealed, was developed by 7 property developers, housing associations, mostly in the social sector. They succeeded in taking the changed framework conditions of climate and biodiversity loss as the starting point for planning and, in co-operation with experts who are usually not involved in the planning process, such as biologists, climatologists and ecological system planners, agreed on a joint development plan that would take this into account: The ‘Biotope City concept – the dense city as nature’ was established as the starting point. Around 1,000 flats were built, 65 % of which are in the social sector, 2,700 m2 rooms for communal facilities (library, kitchen, children’s kitchen, studios, halls, Mobilpoint for communal vehicles and means of transport), local supply shops, a school, a kindergarten, restaurants, offices and a hotel; of course, green roofs throughout and, as far as fire protection regulations permit, green façades.

There are even swimming pools on two of the roofs – nota bene on social sector buildings. The entire site is car-free, garages are located under the buildings, which allows deep soil cores for the trees in the open space. All rainwater is retained on the site, and there is a pond as an overflow catchment for long periods of heavy rainfall. (3)

Room for improvement

As always with realised plans, there is room for improvement with regard to follow-up projects, such as the use of too many closed asphalt surfaces, the lack of open watercourses and the exclusive use of concrete in the architecture. However, the success of this planning can be seen from the fact that not only the residents make extensive use of the green open spaces, but also people living in the neighbourhood spend their leisure time there with their children, mind you in a district with a GFZ of 3.0 – and this despite the fact that a park directly adjoins the district and you can walk into the Vienna Woods a short distance away.

The scientific team, which accompanied and evaluated the entire process of planning and building of the Biotope City Wienerberg, has summarized its conclusion in a detailed manual: How do you plan and build a dense city as nature? This can be found online on the website of Biotope City Journal and on the site of the University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences. (4)

Footnotes and literature:

- (1) Jaap Evert Abrahamse, De grote uitleg van Amsterdam, Bussum 2010, p. 115

- (2) https://pphp.nl/ project/sluisbuurt-amsterdam/

- (3) the brochure: ‘Hidden Treasures – Invisible Building Blocks of a Sustainable

Stadt’ presents the measures that are not visible when visiting the neighbourhood, but are important components of its functioning, and ‘Bio- tope City – Building instructions for a climate-resilient, green and nature-inclusive city’, Hidden Treasures – Invisible Building, IBA Wien 2022 - (4) Biotope City – building instructions for a climate-resilient, green and nature-inclusive city’ https:// biotope-city.net/wiener-berg-bauanleitung-biotope-city/

This article was first published in German: Ernst & Sohn Special: Regenwasser-Managment (Rainwater management) Berlin 2024.