THE CITY AS NATURE: PROGRAMMING A U-TURN IN ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING

Helga Fassbinder

Lecture at Movium, Swedish Landscape University, Alnarp, Conference ‘Livet i staden 2012’, 26.jan.2012

Beatrix, Queen of the Netherlands surprised the public with a remarkable speech: In her annual Christmas address at the end of 2011 she said:

“Care is not just about individual welfare but about the welfare of all and about the stewardship of the earth. With our precious planet is handled carelessly and what it gives us is poorly distributed…..Selfishness and the desire to create abundance blind to the damage to our natural environment and undermine community. View the finiteness of what the earth can give.”

The message was clear: The nature of the world is endangered. If we don’t act now we will destroy it and this will undermine our society.

This speech caused surprise and was welcomed by most of the scientific community and by the public.

On the other hand there were also enraged letters to newspapers asking whether the Queen had become a spokesperson for the Green Party.

But such reactions remained the exception. In general we can see the trend towards a cross-party consensus regarding the ecological damages we cause.

A good example for this was Germany’s decision to phase out the use of nuclear power plants.

The Social Democratic-Green coalition government initially made this decision already in the late 1990s. The Conservative-Liberal government reversed this decision – only to change their policy again after the disaster in the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

There are however important dissenting opinions as well. Their proponents insist on the primary goal of economic growth and therefore support the continued use of nuclear power until technological advancement has solved the energy problem. Sometimes these positions are clearly motivated by economic interests. In other cases their motives are not as easy to comprehend.

One example is a Star of Architecture and Urban Design: Rem Koolhaas.

In an article published in the Harvard-Reader “Ecological Urbanism” he distinguished two competing positions in architecture and urbanism: advancementand apocalypse.

In his eyes: there is a dichotomy between rationality ( the basis of advancement) and attachment to Nature (the basis of apocalyptic thinking). This dichotomy could be identified throughout European history, he says. And today apocalypse presents itself in the form of green positions.

Koolhaas argued that the warnings concerning Nature and the viability of human life on earth lack rationality. In his opinion “Progress” through technological advancement is still the way to solve global ecological problems. He dismisses Green solutions as little more than window dressing and he even uses the term Greenwash.

It seems as if the critical discussion on the concept of progress, on the limit of growth and on sustainability of the last decades have eluded him. Meanwhile Mr. Koolhaas was interviewed by the German Newsmagazine DER SPIEGEL. The occasion was the completion of the Hafencity (Port-City) in Hamburg which has almost no “green architecture” elements. The interviewer asked , “What do you think of this architecture which seems to be looking the same all over the world ?”

The answer was about: no problem, on the contrary, this can be beneficial in times of unprecedented mobility. Since many people all over the world move to far away cities, often for a limited amount of time, the international architecture makes it easier for these people to feel at home anywhere in the world.

This is an argument that is a hundred years old and is deeply rooted in modernity. It is hard to imagine that Mr. Koolhaas has missed the alarming predictions which prompted Beatrix warning.

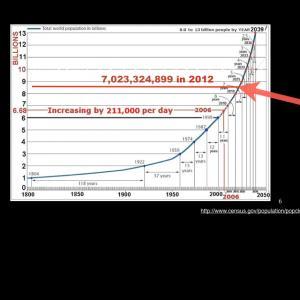

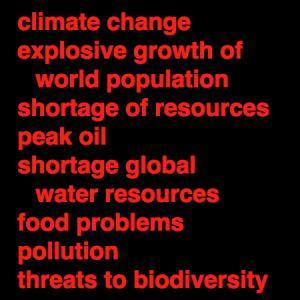

I only give two illustrations, one of the global human polulation growth and a list of catchwords of global problems.

Is his main aim to argue against fatalism, which some people have undeniably fallen into? Is it possible that his negative view of a green turn is correct? Are we really just dealing with fashionable “Greenwash”? Isn’t it the way of both, new technology and an intelligent use of natural forces as f.i. green?

Or are his views simply explained by the fact that his firm currently lacks the skills to compete with the firms of Foster, Ken Yeang, Woha and others?

The conservatism of many architects and planners seems to be motivated in part by a lack of skills in the rapidly growing areas of “green building” and “green planning”.

I would very much like to lay aside Rem Koolhaas statements with amazement and continue working on the areas I regard as important in our times, even though they might be associated with fatalism and possibly also regionalism.

But since these views where brought forward by an influential representative of our discipline I feel obliged to criticize these statements in detail.

Did the highly acclaimed combination of internationalism and rationalism and the mass of buildings, it produced, really lead to such impressive results in the past?

A look back in the history of mass housing construction after world war II

Let us take a look back at modern, rationalist construction after the Second World War. Starting point was a high level of housing shortage all over Central Europe immediately after the war. The Construction industry had to provide housing in large numbers and in a short amount of time. Rational housing construction came to be predominant throughout Europe.

This of course had its impact on the quality of housing. Already beginning in the 1960s a younger generation of architects started to criticize this path.

Criticism was voiced from three different directions:

– Missing involvement of residents

– Use of unhealthy materials in construction

– Disregard for natural conditions

Already at the eind of the 50s young architects with – later – great names rebelled against the chilly rationalism of CIAM.

They etablished the group Team 10: They wrote:

“Functionalism has killed creativity and is leading to a chilly technocracy, where the human is forgotten.

A building is more than listing functions; architecture has to make human activities possible and has to support social contacts”.

Already 1961 the young John Habraken explored the industrial construction product that would be offered to those searching for flats prefabricated, without the option to account for the consumer’s preferences. Habraken goes public with the idea to separate the basic construction from the built-in components. Here he spots the possibility for the future inhabitants to decide on their flat freely and directly – participation in industrialized domestic construction. His book “De Dragers en de Mensen” (“Supports: an Alternative to Mass Housing”) became famous allover the world and was translated into many other languages.

The concrete sphere of building materials also meets with criticism. In Germany, the physician Hubert Palm gave building biology a push with his book “Das Gesunde Haus” (The Healthy House), published in the 1960s. This has been grown out to a movement among young German architects. It leat to the “Institut für Baubiologie” (Building Biology Institute) which is being founded in the seventies finaly. His approach focusses on the impact of materials within the house and in the surrounding field on people. Building Biology has become a specialization among architects by now. Today this approach is part of the objectives of sustainability.

In the 1960s Jacob Bakema, Aldo van Eyck, Herman Hertzberger and others established the “Forum Group”. They expanded their critique to another issue:

the neglect of environmental conditions. They demanded to examine the natural environment too and to let the elemental forces play a part in constructing.

In 1965 Bernard Rudofsky attracted international attention with the exhibition “Architecture without architects” in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Rudofskys collection of examples is one big appeal to start building projects from the local circumstances and to take the natural conditions into account. The exhibition cátalogue became a famous book untill today.

In 1969 Ian L. McHarg published “Design with Nature” – an early call for ecological planning – indeed he already used the term “ecology”, and his book still is considered as a “bible of ecological design”.

However these countermovements and wake-up calls had little impact.

The mainstream of building moved forward on the track of advancement, the so-called rationality of industrial constructing.

The reasons why these signals were ignored…….? It still is going on…. should I call it ‘advancement’?

Mankind and technology – a philosophical discussion

In the sixties, paralleling these protests there was a discussion concerning the relationship between humankind and technology, respectively nature and technology,

The position of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger is still of interest today:

He regarded modern technology not only as a neutral means to answer a purpose, as it was common in this time. Instead he tried to show that technology also induces a change in our perception of the world.

According to him technology directs us to look at the earth mainly under the perspective of utilisation. Because of its global distribution and the ruthless consumption of natural resources, caused by the woreldwide expansion of modern technics, Heidegger considered technology to be a peremptory threat.

This could sound like technology pessimism first of all – and that’s the way Heidegger was understood by many.

However, in his lecture “Die Kehre” (the U-turn) Heidegger distanced himself from the insinuated pessimism concerning technology. And he emphasized that modern technology is also a way of revealing – that means: making the secrets of nature and their laws visible. It is not only a threat, but also includes the salvation.

The only thing humans have in situations of extreme danger, says Heidegger, is their awareness of being in danger. There he sees the chance for a U-turn – the chance for us to recognize our alienated relationship to nature and to decide to change our ways.

I understand this as the chance for a U-turn in our discipline: returning to respect nature, to respect all forms of existence. And returning to a technological development that tries to adapt with the conditions of nature in her cyclical regeneration. This because our main aim has to be to keep the natural conditions of our environment stablized.

In my opinion the threatening global risks should not be understood as apocalyptic scare tactics, but should help us to acknowledge the danger.

By acknowledging it we can react rationally by searching for techniques and processes that help us to re-install stability in our relationship with nature. Herein I see what Heidegger calls “Salvation in the consciousness of highest danger” (“Rettendes im Bewusstsein höchster Gefahr”).

Coexistence between nature and technology

What does this imply?

It implies much of course – take only the difficult and far reaching discussion about a possible zero growth under a threatening shortage of natural resources, which is going to come up among economists, as Stieglitz and others.

Let us only regard what it could mean in our discipline:

Take the simple example of climate conditions inside a building:

It means f. i. using natural air flow instead of air conditioning – as it is still common today, not only in warm countries or areas with hot summers (like New York) but also in central Europe.

Rudofsky has pointed out, how natural winds are catched to ventilate traditional houses by placing wind collecting openings within the main wind direction.

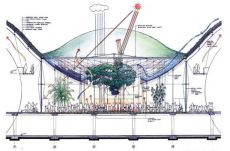

I see a connection between the demands of the “Forum”-Movement and Rudofsky’s reference to native building to the skyscrapers without air conditioning systems, built by Ken Yeang and Woha in subtropical areas .

With their “green hightech projects” they go for a different relationship with nature – a relationship that preserves nature, that tries to walk the talk of “Baubiologie” with most advanced methods.

Instead of the dichotomy of advancement and apocalypse I see in these buildings a new, encouraging connection between technology and nature, fare from the perception of threat – a connection that does justice to the variety of environmental conditions and the diversity of people and their social constitution.

This new connection could be the “salvation” be seen, the “Kehre” = U-turn in the way Heidegger sensed it.

The city would no longer be the place where nature is exploited and where the exploiters gather. The city would rather become a place of re-integration of nature and coexistence with it’s most active and most dangerous creation, the human being.

First approaches of this coexistence are already observable:

Biodiversity is higher in cities compared to the countryside. On the one hand this is definitely an effect of the exploitation of nature by agricultural economy that has led to a dramatic depletion of our rural environment; flora and fauna are migrating into the cities.

On the other hand it is also a consequence of the plurality of life conditions in the cities. Not only we as humans in all our diversity produce, need and enjoy this variety –all the other species of organic life: flora and fauna do so, too.

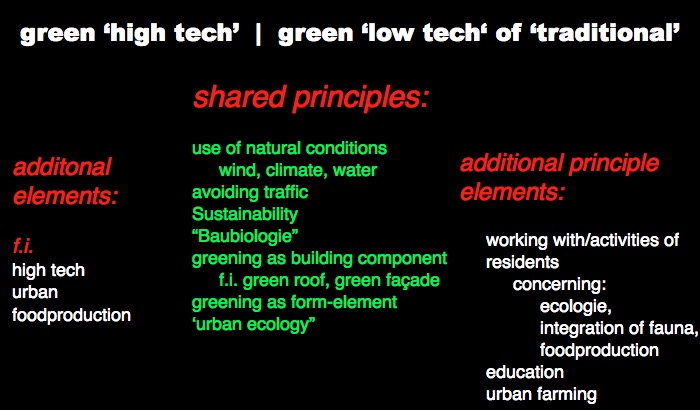

This new coexistence of “city” and “nature” overcomes the antagonism between high tech and traditional procedures – it rather connects both ways. “Greening” is the observable expression of this coexistence.

So why is there still defense against “greening” among architects, like Rem Koolhaas articulates it?

There are well-known architects that do not show this defense: It was only lately that some leading architects started experimenting with green, including the aesthetic dimension.

Famous all around the world became the two results of the cooperation between architect Jean Nouvel and biologist Patrick Blanc.

Edouard François, Ton Venhoeven, Renzo Piano, and Stefan Boeri are other well-known architects working with “greening”.

There is a “modern” green tradition in Asia as well: widely famous became the Acros Building in Fukuoka City and Next 21 in Kyoto, that experimented with green already in the 1990s.

Vertical green is being applied between skyscrapers, for example by Ken Yeang and Woha.

Wong Mun Summ, one of the founding architects of Woha, proudly emphasizes: “natural air conditioning, and no loss of land!”

About Ken Yeang one could read in the NYTimes: “The hanging gardens of Ken Yeang have brought a new aesthetic to the design of skyscrapers. More than that, they have brought a new ethos of sustainable design to the building type. His ‘bioclimatic’ towers have an impact around the world, fusing high-tech and organic principles that have grown out of a response on the harsh and humid climate of his native country – Malaysia….”

Today we can state: in all corners of the world there are green experiments and samples, on the high tech level as well as in traditional building and on grass root level in everyday life. And this is not by chance:

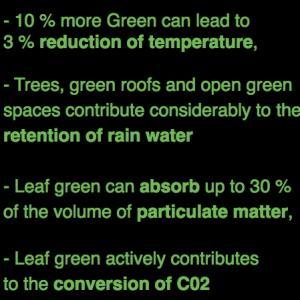

Living green in a densely developed urban surrounding has many positive effects – on the climate as well as on the physical and psychic health of the townspeople.

I suppose I don’t have to explain that to you in detail any more…. regard this list of advantages:

Reduction of temperature, 10 % more Green can lead to at least 3 % colder; green has as an effect a retention of rain water during downpour; it absorbs of particulate matter; and last not least leaf green actively contributes to the conversion of C02.

A green skin for the city

What’s needed to do, is to create a green skin for the city. That is efficient, energy saving, improving climate, it is low cost, it supports the experience of civil society, and last not least: it is beautiful!

There are many of green components to use and to play with:

trees, green roofs, vertical green, plants on balconies and windowsills, small gardens at the base of trees, uncontrolled growth of wild herbs (formerly called weeds) in each and every gap, green on communal fallow land, finger parks, pocket parks, etc. and of course urban parks, and – a recent development – urban edible green.

By the way: urban ‘farming’ by residents is an important new item. All over the woreld, also in the western countries, you can find people busy with vegetable – not only on their roofs and balconies, but also on common green in residential areas.

Collectief gardening is a marvellous initiative building up a civil society in a multicultural area which combines foreigners and native people of all social classes.

There are exiting examples of gardening together in social problem neighborhoods with many different ethnicities.

All this is not a question of traditional forms of constructing against hight tech.

Both share the same main principles.

For both are reasons to regard city as nature: as one of the many types of landscapes like savannah, heathland, wood, desert etc..

The type ‘city’, as a type of nature, is the space of a dense cohabitation of the human species with other forms of life, with flora and fauna.

Actually the city is nothing else than an extreme kind of a rocky biotope – an overcrowded rocky biotope….

For both technical approaches, the high tech and the low tech one, the main aim has to be: to return to a cyclical thinking, as nature is based on.

On the one hand “city as nature” is a building challenge. Architecture and town construction can contribute to the minimalisation of environmental problems on different levels.

But on the other hand “city as nature” is also about responsibility and behavior.

It is also a program for the civil society. “Greening the city” is viable only in cooperation with the inhabitants. Administration alone will definitely fail.

Fortunately, green roofs, vertical green, plants on balconies and windowsills, the marginal growth of wild herbs etc. enjoy great and growing popularity nowadays – many people appreciate that.

“Greening” is meanwhile about to come into fashion – with some strange effects sometimes….. Do you already wear a planted ring?

Let’s hope this fashion contributes to a “greening” break-through in architecture and the building industry….

Actually, “City as Nature” is a fact that spreads out, AND at the same time it is a program for the civil society!

Regarding the numerous arguments for integrating green in architecture and urban planning, my suggestion is :

Nominate living green as one of the common building components and let it rank equally with stone, concrete, steel and glass !

But we are still quite far from this practice yet…

Reluctance among building industrie and architects

Why is the construction and architect community so hesitant here?

Apart from ideological reservations there are some reasons for being reluctant. I see a couple of motives:

1. The construction component “green” is alife and dynamic – other than all the static construction components that show only small and calculable changing in time under the influence of use, sun, heat, cold, rain…

Another problem: Living green askes maintenance. This is not extremely expensive, but it has to be taken in account.

2. In addition to this, green never exists alone: flora and fauna are irresolvably linked up. That means: no green without insects and birds.

(We are not really afraid of spiders, are we?) And what about the wild animals in the city?? In Berlin are about 3.000 wild pigs enjoying their life…

3. Many architects and urban designers don’t have many clue about plants, not to mention insects and birds. Still they need the support of ecologists and biologists…

4. Another problem is – and this plays certainly an important role: You can see the final result of a greened building not yet at the point of it’s technical completion. The plants need time to grow.

5. Greening is often more expensive for a start – even if it proves cheaper on the long run, as with green roofs.

Furthermore parts of the profits of “greening” inure to the benefit of the community – not only of the individual investor. Greening is partly a social act as well. (But this is the same with the beauty of a façade…)

6. There is some reluctance concerning the waterproofing thermoplastic foils. There is made huge progress during the last decades. But nevertheless nobody is able to tell exactly how long it takes until the material may embrittle.

Apart from these reasons there is one more I want to mention: the different view on aesthetics. Since the general breakthrough of modernity that set off for its triumphant success a century ago we became used to plane aesthetics with no ornaments.

‘Ornament is Crime’ declared the influential ‘modern’ architect Adolf Loos – and that is the attitude of many generations of architects untill now. Architects are being educated by and towards this aesthetics in their schools.

It is so self-evident: we find it hard to imagine that the sense of beauty of the 19th century – borne by a general enthusiasm on decoration – could not only be considered as a historical phenomenon, but that we might restart a timely kind of “decoration” from there. And such an up-to-date-form of “decoration” can be found in the wrapping of buildings with living plants.

By the way – living covers for buildings have been used for centuries now, for aesthetical as well as climatical reasons. Vertical green is a traditional way of beautifying unsightly or tedious walls, and evergreen ivy has been used to protect walls against the weather since long.

What to do ?

What can we doe to stimulate greening against these doubts? I see 4 strategies :

1

spread knowledge about the positive effects of greening – there is still an enormous lack of knowledge!

2

spread the knowhow of greening, just: how to do it, which plants need what and will do what…starting with simple and cheap forms and going on to technical details and high tech possibilities

3

stimulate organizations and political parties to support obligations of green roofs on nieuw building by decrees and orders

4

support residents and action groups for greening in all forms

What answer do we have to these objections? What can we do to overcome the reluctance born out this motives? Certainly the answer has to be close to each project in question. Generally spoken we have to work on a change in attitude – a long run turn of course, but nevertheless it is possible and it already has started (and think about the big changes in attitude and thinking already have taken place! a few decades ago most of the people could n’t belief that the separation of domestic waste by households could be a realistic perspective – and now everybody does or at least is obliged to do…) So it will need some time in this case, too

Meanwhile there is a strong support by plant experts and garden firms. Since they have recognized that there is a market for green, and that they can make money with green roofs and vertical green they show interest in this.

Precursor of the vertical gardens was biologist Patrick Blanc who for several years now carries out spectacular projects all over the world. He developed an expensive system for this, protected by patent.

In the meantime there are numerous other systems for vertical greening available on the market.

Nicole Pfoser of Darmstadt University, Germany, has researched the possibilities to realize vertical greening, and has developed a methodical and most useful classification of these options – from simple ways by using clamperers like ivy or Virginia creeper, to elaborated systems, placed in front of the wall with electronically controlled irrigation.

This is a very usefull scheme – much to detailled for now. I invite you to surf to this scheme – there you can find it together with a text by Nicole Pfoser, which give explanations.

Coming to a conclusion: In spite of the economic crisis there are reasons for optimism. A first step of a U-turn has started already: Sustainability is a worldwide goal for quite some time now, and thanks to decrees and codes it slowly becomes standard.

And things are moving on:

Greening has appeared as another goal.

“Greening” represents a next important step of re-thinking our relationship to nature and to technique under the essential basic conditions of upcoming shortages we are subject to.