The Relationship between City and Nature in History

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

Peter Joseph Lenné (1789 – 1866) is unquestionably famous as a great landscape architect (Fig. 1). His contributions to the planning of the urban expansion of Berlin are less well known, although they had a great influence on the urban development of the city. On his trip to England in 1822, he had been able to study in London the role that parks, green spaces and squares played in the development of a large metropolis and how little it had been taken into account in Berlin until then.

“How much Berlin suffers from a lack (of public greenery) is well known. Apart from the promenade Unter den Linden and apart from the Tiergarten, the capital has no public esplanade where the industrious craftsman, or the busy factory worker could go in the evenings and on Sundays after a day’s work. This lack is evident in the entire northern and southern parts, i.e. precisely in those areas of the city that are the headquarters of the industrial class.” 1

That Berlin is so green in so many parts is also thanks to Lenné and his foresight (Figs.5,6).

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

To this day, we can experience neighbourhoods within the city that shape Berlin’s image as a “green city” alongside evidence of the “stone city” (Figs.7, 8).

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

Archive: Herr Schultz

Archive: Herr Schultz

Garden City Movement

Long before Werner Hegemann bitterly lamented the excesses of the development policy of the second half of the 19th century in Das steinerne Berlin, there had been strong counter-movements in the city. Influenced by Ebenezer Howard’s ideas on the garden city (1898), new urban concepts were developed after the turn of the century.

The competition Groß-Berlin 1910 promoted discussion about urban green in particular, as green space played a key role in the conditions and goals of the competition announcement.

Vienna was cited as a European example. As early as 1905, a decision was made to create a forest and meadow belt around Vienna. The competition entries for Berlin demonstrated the intertwining of green space and urban structure in very different typologies. The first prize-winner – Hermann Jansen – for example, countered the idea of sharply defined urban areas with flowing open spaces. He interwove his concept through the entire urban region with the aim of offering every citizen a green space not more than 2 km away2.

At the same time, alternative ways of linking urban living and open space at a smaller scale were introduced in new residential areas. In Berlin, the Rheinisches Viertel is a representative example.

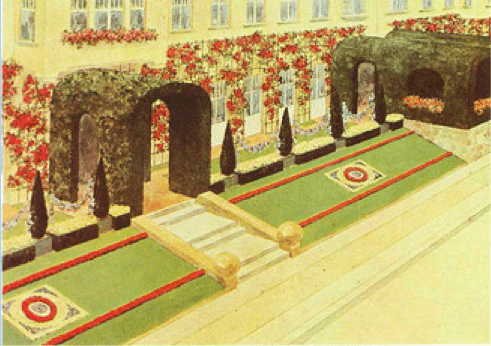

With the Rheingauviertel, the Terrain-Gesellschaft Berlin-Südwest under its managing director Georg Haberland3 built an urban “garden city” in Wilmersdorf beginning in 1905; in this case the garden is conceived as a public decorative green. In order to achieve a cohesive yet individual character for the four-storey blocks of rented flats, a single architect, Paul Jatzow, was engaged for the English country house style façades, while the flats themselves were planned by other architects.

The streets of the quarter are still characterised by the façades with high gables and front gardens and the thirteen-metre-deep so-called “garden terraces” that rise slightly toward the buildings. Originally, the greenery of the terraces was to continue as a vertical trellis on which roses were to climb up to the first floor of the houses (Figs.9, 10).

The Land Use Ratio (GFZ) of the residential complex, which is still very popular today, is around 2.0.

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

First Environmental Movement

Green neighbourhoods for workers and minor employees followed immediately after the First World War, here the focus was on “social” greenery.

Decisively responsible for this development were Martin Wagner and Leberecht Migge. Martin Wagner (1885-1957), who in the 1920s became a leading city planner, published his dissertation Das sanitäre Grün der Städte: ein Beitrag zur Freiflächentheorie in 1916. The dissertation referred to a discussion about the hygienic value of green spaces that was current in Germany at the time. Wagner tried to work out criteria that would determine a minimum amount of green space in relation to population density. The quality of green spaces was no longer determined by their decorative value but in their value for recreation, sport, and self-sufficiency through the cultivation of fruits and vegetables.

Leberecht Migge (1881-1935) began working as a freelance landscape architect in 1913. He had already joined the Deutscher Werkbund in 1912. Encouraged by the contacts he made there and by planning various public parks, Migge developed his own theory of the role and function of landscape architecture. In his books Die Gartenkultur des 20. Jahrhunderts (1913) or Jedermann Selbstversorger (1918), he presented his ideas about the social function of urban green space and further developed the idea of the garden city into his own particular model. In his view, it should be possible to develop cities as “autonomous beings” without exploiting the surrounding landscape.4

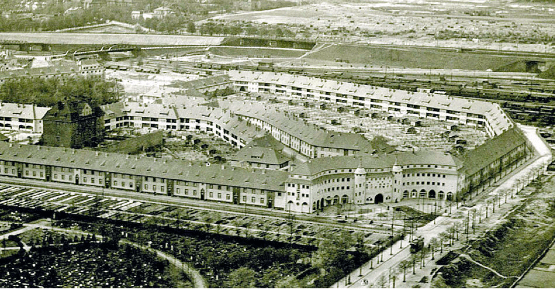

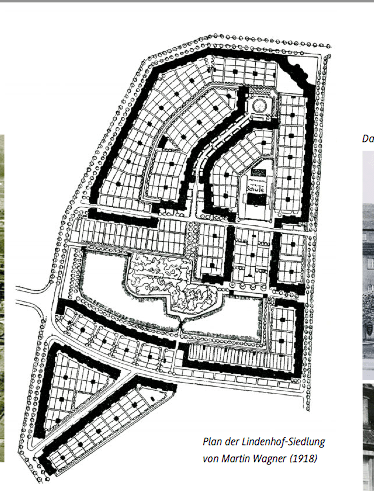

In Julius Posener’s lectures, the Lindenhof housing estate in Tempelhof-Schöneberg, built between 1918 and 1921 in the immediate vicinity of the Priesterweg S-Bahn station, is cited as a particularly striking example of the integration of housing and green space and of the collaboration between Martin Wagner and Leberecht Migge.5

The developer of the estate was the city of Schöneberg, which was independent until 1920. Subsequently, the estate became the property of a cooperative founded in 1921 (Figs.13, 14).

Archive: Gewosüd

Poto: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

In 1926, Martin Wagner moved to Berlin’s central building authority as a city building official. Under his leadership, the city planning office, in close cooperation with newly founded non-profit housing societies and with the help of the building interest tax he introduced in 1924, was able to implement an extensive housing programme in which open spaces were placed in close proximity to the flats. An example of this is Bruno Taut’s Hufeisensiedlung, again with Leberecht Migge as the open space planner. The concept of “outdoor living space”, coined by Bruno Taut, is realized here in a particular way as a social open space where residents can meet (Fig.20). Six of these settlements have been World Heritage Sites since 2008 because of their innovative combination of urban planning, architecture and garden design.7

Photo: Inken Baller

In the Bauhaus Year 2019, an examination of the Bauhaus contribution should not beoverlooked. Ecological aspects unfortunately appear only very marginally in this context, but the housing estates in Dessau – which are often wrongly attributed to the Bauhaus, but were built by the Anhalt Settlers’ Association and planned by Leberecht Migge and the architect Leopold Fischer (1901 – 1975) are a fresh discovery. Fischer was a master student of Adolf Loos, whose life and work are only now gradually being researched.8 He was exposed to and studied the principles of economical building with Loos in the Viennese housing projects. In 1925 he accepted an invitation from Walter Gropius to come to Dessau to work in the Gropius construction office. He mainly influenced the initial phase of the Dessau-Törten settlement.

According to diary entries by Ise Gropius, there was a disagreement: (…fischer, who had worked in g.atelier for some time, but was then dismissed because his skills were too low and because he could not face Neufert.)9 Fischer left Gropius and subsequently served as chief architect of the Anhalt Settlers’ Association from 1925 to 1931. The contemporary disputes about the Törten settlement (excessive costs, construction defects, functional errors…) played a role for decades, and the positive qualities and broad acceptance of Fischer’s settlements were not appreciated. As a result, the achievements of the settlers’ association were hardly known beyond Anhalt.

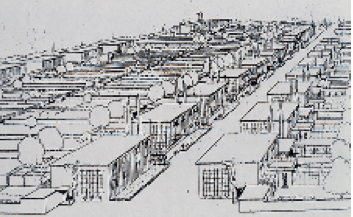

The Knarrberg settlement in Dessau-Ziebigk in particular can be seen as a counter-design to Törten. Leopold Fischer and Leberecht Migge planned and built a two-storey semi-detached housing estate in a modern design language with glass-roofed conservatories and 400-square-metre kitchen gardens, separated by man-high wooden fences, also called fruit walls, and a rainwater infiltration system. Leberecht Migge had drawn up an optimised plan for each family to be self-sufficient and for the household waste to be reused in the gardens (Figs.21, 22, 23). Therefore it was also called “the Self-Sufficient Settlement” (“Selbstversorgersiedlung”).

Archive: Museum für Stadtgeschichte Dessau

Archive: Museum für Stadtgeschichte Dessau

Archive: Museum für Stadtgeschichte Dessau

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

Archive: Fabian Zimmermann

Urban Utopias

In the 1950s and 1960s, the increasing urbanisation in the world was seen as a threat to the future of humanity. The traditional urban concepts were deemed unsuitable for accommodating the explosively growing population. New visionary city models were developed: mostly hybrid, highly engineered structures. In parallel, ideas emerged that saw themselves as a continuation of natural conditions, such as those of Paolo Soleri, (1919 -2013), the inventor of the Arcology movement and builder of Arcosanti in the Arizona desert. In his visions, people should live self-sufficiently and compactly in harmony with nature, using the desert wind and the sun as energy sources.

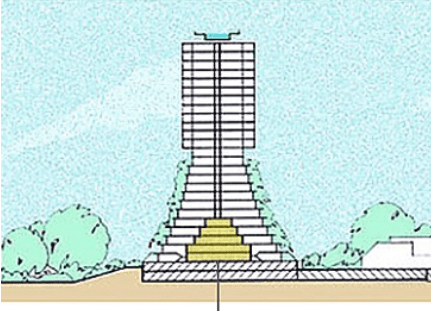

Around the same time in 1965, Enrico (1925-2013) and Lucia Hartsuyker (1926 -2011) developed “Biopolis”, a model for a new urban culture in contrast to the functionalist city – Biopolis as a socially and functionally integrative compact city with stacked terraced gardens, about 15 storeys high. Hidden inside, the necessary infrastructure for the residents and traffic was accommodated.

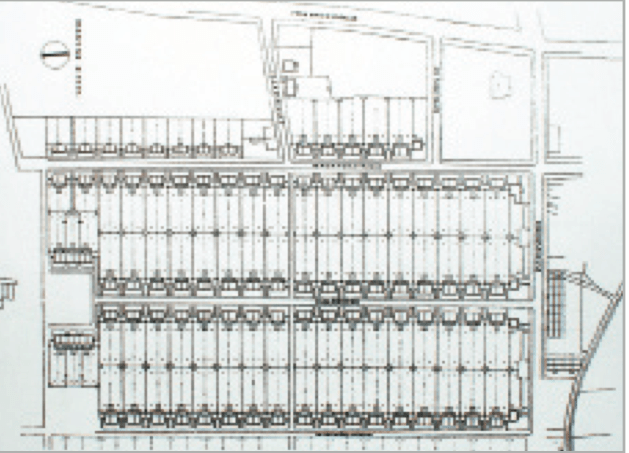

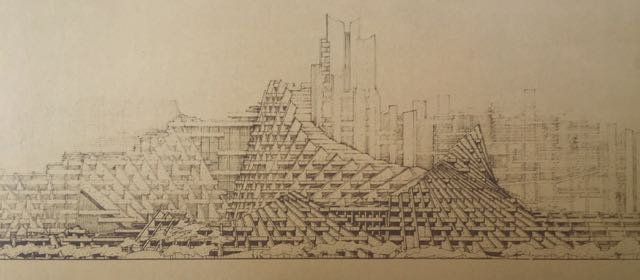

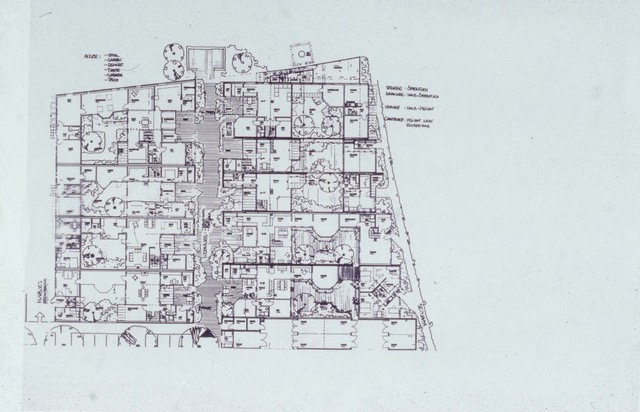

Merete Mattern (1930 – 2007) took part in the urban planning competition Ratingen West in 1967 together with her mother, the landscape and garden architect Herta Hammerbacher, and Yoshitaka Akui. She submitted an urban landscape with the following summarised working theses: Social integration, participation, holistic living, and a close connection between architecture and landscape. The work was honoured with a special mention (Figs.27, 28, 29). In 1972, Mattern founded the “Gesellschaft für experimentelle und angewandte Ökologie e.V.” (Society for Experimental and Applied Ecology).

Archive: Fabian Zimmermann

Archive: Fabian Zimmermann

Archive: Fabian Zimmermann

Photo: Helga Fassbinder

Photo: Helga Fassbinder

Office Harry Glück

Photo: Helga Fassbinder

Alt Erlaa, Vienna

The Viennese Harry Glück (1925 – 2016) planned and built Austria’s largest non-municipal housing estate with 3200 flats in Alt-Erlaa from 1973 to 1985 (Fig.30). Alt-Erlaa can be described as a city within the city – a green city with which Glück deliberately built a counter-model to the usual housing estates. With his terrace houses, the architect wanted to offer city dwellers a substitute for living with a garden (Fig.31). Glück used the interior spaces with no natural light on the lower floors created by the terraces for indoor swimming pools, saunas and solariums, fitness centres, club rooms and bad-weather children’s playgrounds, all within the budget of subsidised housing (Fig.32). The most important places of communication became the rooftop swimming pools with a view over half of Vienna.

In addition, there are medical centres, kindergartens, schools, youth clubs, sports and tennis halls, a theatre, a library, a church and restaurants within walking distance. Economically, this was only possible due to the large number of tenants in a large-scale form. The park landscape between the houses continues up to the 13th floor (Figs.33, 34). Up to this height, all flats have large earth troughs, whose lush planting turns Alt-Erlaa into a vertical garden city.

Much discussed and also controversial among experts, the residents are very satisfied to this day; there is hardly any fluctuation and virtually no vacancies. The high level of acceptance is also reflected in the residents’ noticeable sense of responsibility for their complex.

A comment by Friedrich Achleitner, one of the most influential Austrian architecture critics: “I must confess that I myself only realised very late that Glück had really done pioneering work in housing. Glück has shown that you can’t do housing construction with architecture alone. Many other elements play a role. What he presented is basically an urban concept.” 11

Ivry, Paris

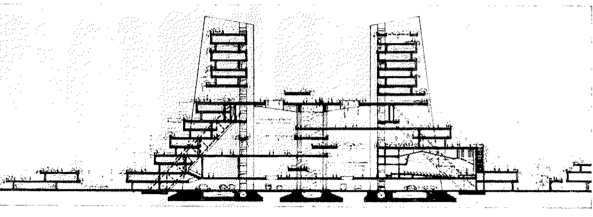

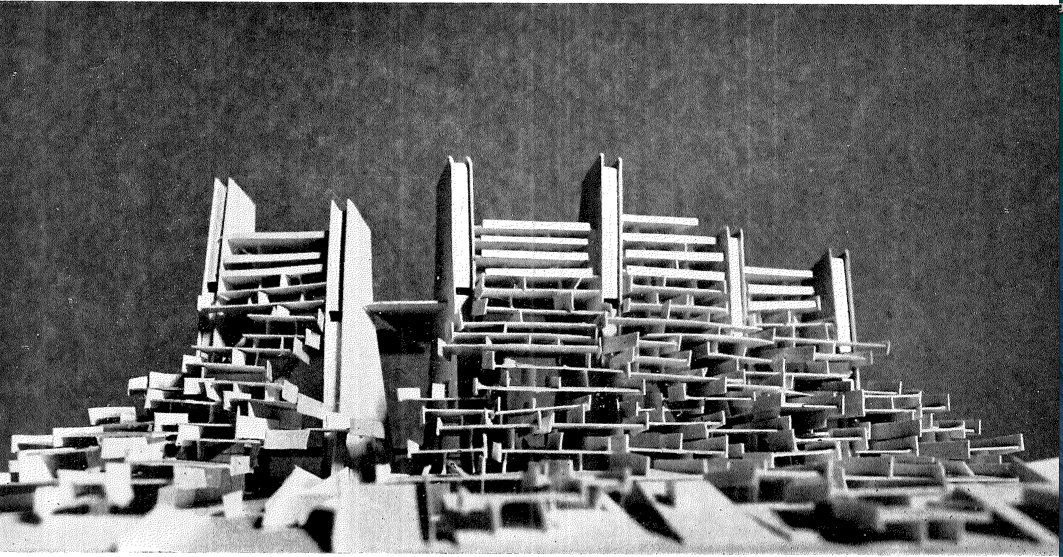

The French architects Renée Gailhoustet (1927) and Jean Renaudie (1925-1981) pursued a comparable approach.12

With their terrace houses and mixed-use residential towers in Ivry sur Seine, they countered in the 1970s the monotony of mass housing construction of the 1950s and 1960s in the suburban settlements of Paris. They brought together private housing and public life anew in social housing. Gailhoustet was appointed chief architect and leading urban planner there in 1969.

Pyramidal structures based on a triangular concrete skeleton grid rise up into abstract mountain landscapes. Each flat has a roof terrace, which to this day is intensively landscaped by the tenants. Inside these structures are the technical infrastructure, the access routes, social spaces such as kindergartens and libraries, and above all shopping centres, which finance the roof terraces. Alleys and paths branch off from the more public spaces to provide access to the individual flats (Figs.35, 36, 37, 38).

Photo: Christian Kloss

Photo: Christian Kloss

Photo: Christian Kloss

Photo: Christian Kloss

Archive: Helmut Rentrop

Archive: Helmut Rentrop

Archive: Helmut Rentrop

Second Environmental Movement

As a result of the oil price crisis, a new awareness of the finite nature of raw materials developed in the 1970s. The second environmental movement received further impetus from Chernobyl and the anti-nuclear movement. In West Germany, it found its institutional expression in 1978 with the establishment of a Ministry of the Environment and the Federal Environmental Agency. In 1980, “The Greens” were founded as a federal party. Against this background, new ecological settlement models were developed.14

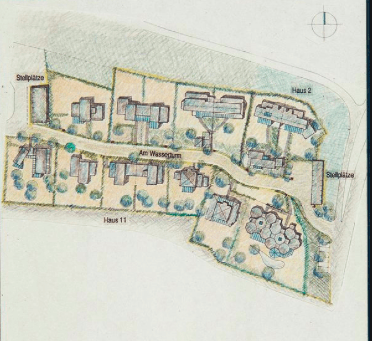

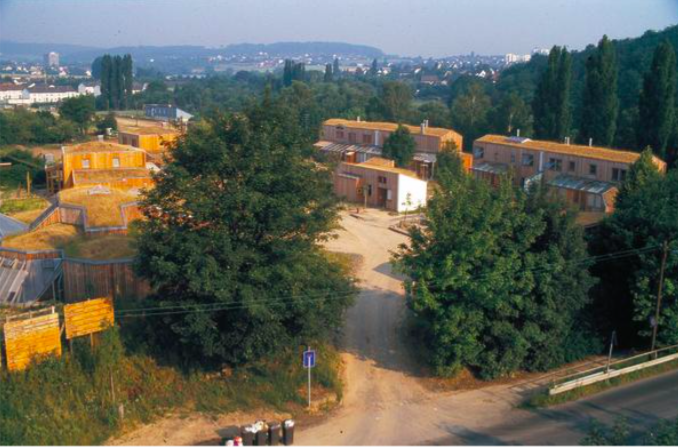

One example is the Laher Wiesen near Hanover by the architects Boockhoff and Rentrup, a housing estate completed in 1984/85 with two-storey single-family houses as terraced houses in timber construction, mostly with supplemental garden outbuildings. It is considered the first housing estate in Germany with exclusively green roofs (Figs.39, 40). A total of 69 flats were built with a high proportion of owner-contributed work and high ecological standards: space-saving construction, infiltration of rainwater, waste avoidance, passive solar energy through winter gardens, environmentally friendly building materials, car-free residential paths, minimisation of sealed and paved surfaces, and economical use of technology (Figs. 41, 42). The garden buildings are also accessed from an additional path at the rear, so that to this day they are used in many different ways: as parental housing, as additional working space, as a workshop or as a retirement home (Fig. 43). The 30th anniversary of the settlement was celebrated in 2014 (Fig.44).

Archive: Helmut Rentrop

Archive: Helmut Rentrop

Archive: Helmut Rentrop

The project shows to this day that ecological building can be based on simple principles and is not a question of budget or expensive technology. In terms of their energy consumption, the houses meet the requirements of the current EnEV (Energy-Saving Regulations). In 1987, Manfred Hegger wrote in a publication on eco-settlements: “Ecological building must also take up social changes and – no less difficult – structure the social organisation of dealing with nature and the environment”.15

Archive: HHS PLANER + ARCHITEKTEN AG

Archive: HHS PLANER + ARCHITEKTEN AG

Archive: HHS PLANER + ARCHITEKTEN AG

Archive: HHS PLANER + ARCHITEKTEN AG

Around the same time, urban ecological examples were realised in Berlin.

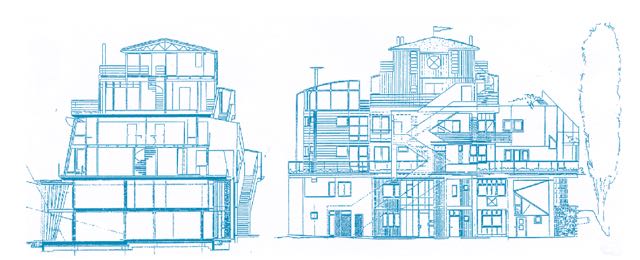

Frei Otto’s eco-houses were built on the southern edge of the Tiergarten and based on the theme of “Nature and Building” as part of the 1984/87 Berlin International Building Exhibition. They were intended to allow the residents a maximum of self-building. To this end, a structure of reinforced concrete was erected and equally stacked building plots were created. Ecologically interested people formed a building community. In addition to Frei Otto, nine architects were active, advising and supporting their respective builders.

Archive: Frei Otto, Hermann Kendel

Of course the lush flora that had developed on the former Vatican embassy grounds after the destruction in World War II could not be preserved during the construction process, but it has since grown back in great diversity (Fig.51, 52, 53).

Archive: Frei Otto, Hermann Kendel

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Ekhart Hahn

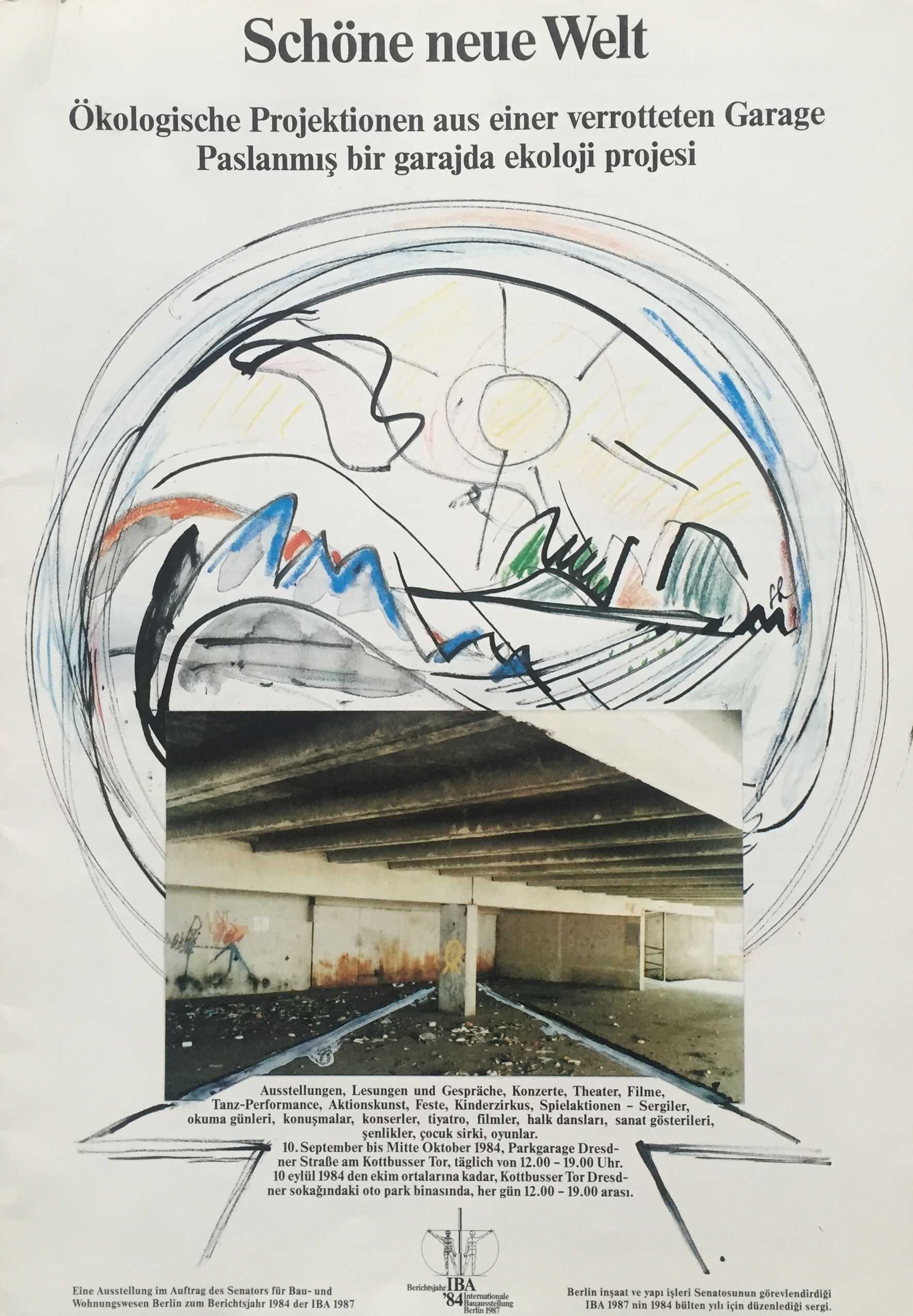

Immediately before the conversion, the elevated garage was used as an exhibition space for the IBA in 1984. An exhibition on ecological issues was shown under the motto “Brave New World” 18 (Fig.56).

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

Archive: Inken Baller

Two levels of the garage were converted as a “nature space” including a fish pond as a demonstration for permaculture by Margret and Declan Kennedy19 and a forum for readings, lectures and concerts was created on the top level. (Figs.59, 60)

Photo: Gabriele Heidecker

Photo: Gabriele Heidecker

Photo: Gabriele Heidecker

Photo: Gabriele Heidecker

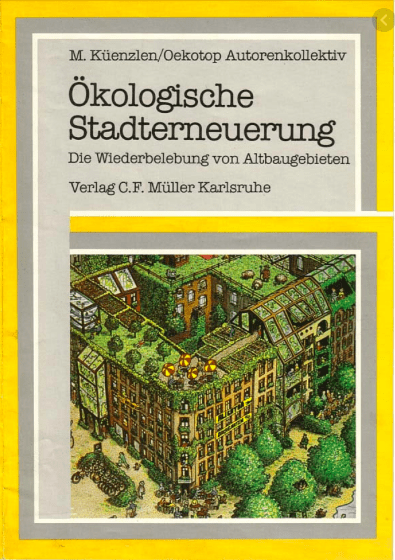

The main structural intervention by the architects Gerhard Spangenberg and Dieter Frowein consisted in the integration of a glazed inner courtyard. The planted inner courtyard and the use of the roof area as a garden are the most important elements of Martin Küenzlen’s20 ecological concept. The planted spaces let forget the building’s history as a parking garage and compensate for the lack of natural landscape in the immediate vicinity (Figs.61, 62, 63).

Photo: Martin Küenzlen

Photo: Martin Küenzlen

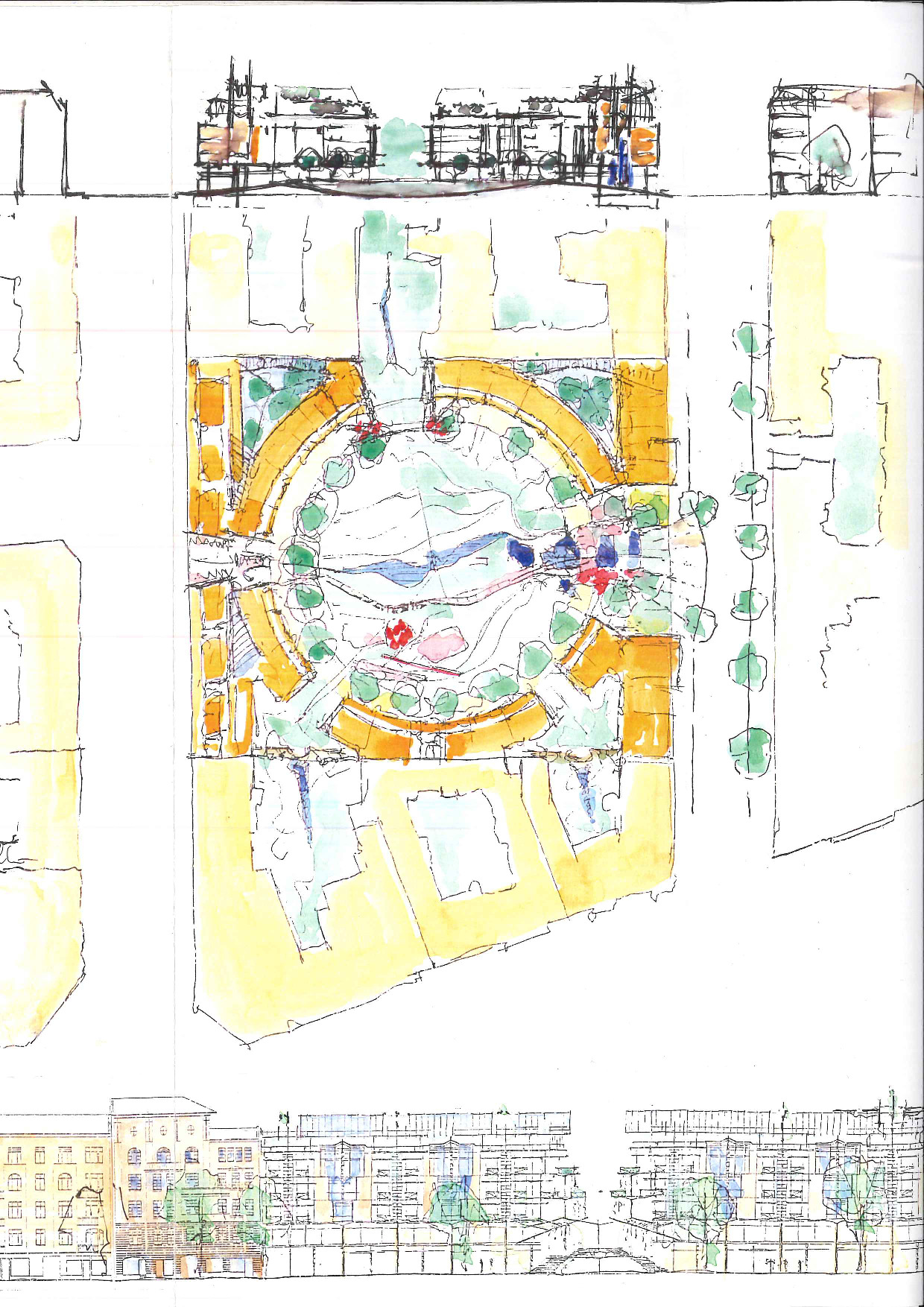

Using Block 10821 in Berlin Kreuzberg as an example, Ökotop wanted to show how blocks of buildings in stony Berlin can be transformed into green oases with the help of large-scale and interconnected planting on all suitable surfaces. For each plot and each house in the 46,000 square meter mixed-use block, a catalogue of measures was drawn up for this purpose as a long-term strategic programme, which, as a vision, is still an on-going challenge (Figs.64, 65).

Photo: Inken Baller

Block 108 is largely occupied by very active commercial interests, less concerned with intensive greening in contrast to the blocks where the majority use is residential, such as Block 103 (Figs.68, 69).22

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

And today:

Hans Stimmann (quote).

“I am a supporter of corporeal architecture, of stony Berlin . . . My architecture must be able to be placed in the line of tradition from Gilly, Schinkel, Messel, Mies van der Rohe, Taut to Kleihues . . . The first condition is: building in a block . . . Wherever I can influence architecture, I understand it under the heading: disciplined, Prussian, restrained in colour, stony, straight rather than curved”.23

Photo: Inken Baller

Photo: Inken Baller

Foot notes

1 Gerhard Hinz, Peter Joseph Lenné, The Complete Works of the Garden Architect and Town Planner in Two Parts, Hildesheim 1989, p.144.

2 Tubbesing, Markus: Die Entdeckung des Großstadtgrüns bis zum ersten Weltkrieg in Bodenschatz, Harald and Brantz, Dorothee (HG), Grünfrage und Stadtentwicklung, Berlin, 2019.

3 Georg Haberland is the son of Salomon Haberland, who founded the Berlinische Bodengesellschaft in 1890, which acquired, developed, parcelled out and sold land to developers. In 1906, as his father’s successor, he merged the Berlinische Bodengesellschaft with the Terrain-Gesellschaft-Berlin-Südwest, which subsequently developed other important projects in addition to the Rheinisches Viertel: for example the Bayrische Viertel in Schöneberg and the Historikerviertel around Sybelstraße between Kurfürstendamm and the S-Bahn in Charlottenburg.

4 Leberecht Migge’s 1932 study “Berlin Colonised”, which will be published for the first time at the end of this year by Karl Krämer Verlag, was a radical plan to produce food within a metropolis itself. With his Berlin Plan, Migge attempted to overcome the ecological crisis of the metropolis, which had been unfolding since the 19th century, with modern means. In doing so, the ecosystem he designed was to be implemented in a step-by-step, participatory manner. (Editor: Philipp Oswalt)

5 Posener, Julius, Lectures, IV Architecture of Reform, ARCH+, Volume 2, Berlin, 2013.

6 BMU press release no.268/16 of 03.11.2016.

7 The following six settlements have been World Heritage Sites since 2008: Gartenstadt Falkenberg by Bruno Taut, Ludwig Lesser; Siedlung Schillerpark by Bruno Taut; Großsiedlung Britz (Hufeisensiedlung) by Bruno Taut, Martin Wagner, Leberecht Migge; Wohnstadt Carl Legien by Bruno Taut, Franz Hillinger; White City by Bruno Ahrends, Wilhelm Büning, Otto Rudolf Salvisberg, Ludwig Lesser; large housing estate Siemensstadt by Hans Scharoun, Walter Gropius, Hugo Häring, Fred Forbat, Otto Bartning, Paul Rudolf Henning, Leberecht Migge.

8 Leopold Fischer was “rediscovered” through the activities of Dr. Irene Below, Dr. Wolfgang Paul, Franz Wolter and others, beginning with the 1994 exhibition “…there was not only the bauhaus.” Particularly informative is the biography on Fischer published in 2010 by Bauhaus Dessau e.V.: “Leopold Fischer – Architekt der Moderne. Planen und Bauen im Anhalt der 20er Jahre (Planning and Building in Anhalt in the 1920s), Funk Verlag, unfortunately out of print in bookshops but available as a pdf on the internet.

9 Gropius, Ise: Diary, entry from 05 June 1926, p. 136, Bauhaus Archive Berlin.

10 A very detailed description of living in the settlement can be found in the previously mentioned biography “Leopold Fischer – Architect of Modernism” by Fritz Becker “Living in the Knarrberg Settlement” as memories of a first-time resident.

11 Seiß, Reinhard: Am Menschen orientiert, Bauwelt 5, 2017.

12 The most important works besides the settlement in Ivry with the residential towers are Raspail (1963-68) and Jeanne Hachette (1972-75) with shops, artists’ studios and workshops and the terrace settlements Le Liégat (1971-82), Marat (1971-86) and La Maladrerie (1975-86). Due to the close collaboration with her partner Jean Renaudie, Renée Gailhoustet remained in his shadow for a long time. She is not mentioned in early publications, for example..

13 arch+ news, 29 January 2019

14 A compilation of the most important settlements of this period can be found on the internet at https://siedlungen.eu > oekosiedlungen

15 Grewe Rosa: …getting on in years, Ökosiedlung am Wasserturm in Kassel, db deutsche bauzeitung, 04- 2010.

16 Der Spiegel: p. 239, No.39, 1984.

17A good summary of the project’s goals and implementation can be found at http://www.ekhart-hahn.de/Content/1/Link/Oekohauuser_Rauchstraße_Berlin-Tiergarten_.pdf Ekhart Hahn was project manager until 1989 and, together with Dagmar Gast, Gabriele Güterbock, Norbert Müller, Peter Thomas, Alessandro Vasella and Joachim Zeisel, responsible for the ecological concept.

18Part of the exhibitions for the reporting year 1984 of the International Building Exhibition 1987, conversion concept of the garage by Bernhard Strecker, adopted by Inken and Hinrich Baller, artistic advice: Gabriele Heidecker.

19Margrit (1939-2013) and Declan Kennedy (1934) are pioneers of permaculture in Germany. They are initiators and co-founders of Lebensgarten Steyerberg e.V. (1986), a living and working community that sees itself as a model and research project for living in harmony with nature.

20Küenzlen, Martin/Oekotop Autorenkollektiv: Ökologische Stadterneuerung – Die Wiederbelebung von Altbaugebieten, Karlsruhe, 1985.

21Block 108 in Berlin-Kreuzberg is an urban planning and urban ecology model project as part of the International Berlin Building Exhibition, funded by the Experimental Housing and Urban Development Program, completed in 1991.

22Hans Stimmann in an interview in Baumeister, issue 7/1993.