Biotope City – the Gardencity of the 21thCentury

Helga Fassbinder

‘Keynote of the Symposium STRANGE PLANTS ARE MY HOBBY ‚COPYSHOP OF HORROR – A temporary space for the nature of cities and the cities of nature‘ by COPY&WASTE at Ku’Damm Karree Berlin, November & December 2017.

The formula “the city as nature” demands a definition of what is meant by nature. Where to start? What to expect? The question is explosive, especially among biologists, but also among ordinary mortals: what is ‘to save ‘nature’, what does this mean? The state 100 years ago? Or should one even go further back? May trees grow on the West Frisian islands that were not found there 100 years ago? What about the neophytes, the plant exotics such as the Indian balsam, the knotweed or the giant hogweed, or with the animal invaders, the Nile geese, the racoons and others? And what role does man play in this concert, who so effectively intervenes in ‘nature’? Here, too, ideas are very different, even controversary – one can philosophize in different ways about what man is: The crown of creation, whose mission is to subjugate the earth, that is to subjugate nature. Or is he a cancer that overgrows the earth and destroys the habitat of such wonderful animals as the Siberian tiger and others, building his own ecosystem against the ‘nature’ of the earth. But one can regard the ever expanding vertebrate species homo sapiens as one of the elements of the continuous process of change of the organic and the inorganic on earth, too.

From the latter point of view, the question is not "how to save the threatened nature and stop the expansion and appropriation of man", but one asks: "How can we set up and regulate the human habitat in such a way that he can spend his lifetime in a good and healthy as possible way, in interaction with other types of life.

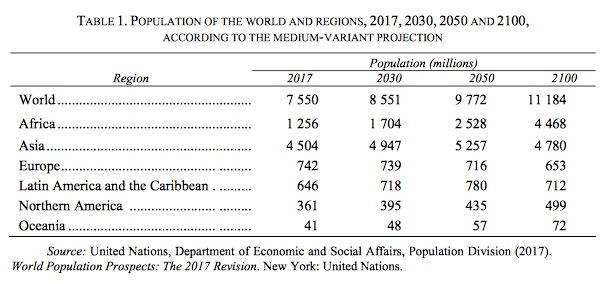

We are not the first to ask this question, as this beautiful medieval embroidery picture shows – people seems to be tiggered by this question in the middle age as we are in the present reflecting the reality of our cities now and in future. Urban reality shows our sharing urban space with nummerous other species, from insects to mice and bird. But if we have to share this habitat with so many other beings, what should the formula be to share our urban living space in a way that would bring so less harm to al participants in city life? How to build and manage the city in a way that it is worth living for all beings, from homo sapiens to flora and fauna? By 2050, it is very likely that around 10 billion people will populate this globe, over 70% of them will live in cities. These cities will spread over huge regions. What will nature be, what is city then? Can we seperate it? Isn't it that the city is and will be a kind of nature? Isn't it better to talk about 'the city as nature'?Being in Berlin at this moment, lets have a quick look back: Take the Berlin mascot, the bear, as a starting point. The Berlin bear gives a hint to the elemental threat we humans once experienced in the wild, in the endless forests of Europe with their bears and wolves.

The people have surrounded their homes with protective walls. The city was surrounded by fortification walls – the human settlements were protected not only against human enemies, but they were also a fortress against nature, against the threat of wild animals. Our fairy tales still are telling about this, about the fear of going beyond the walls, walking through forests where the wolves and bears are waylying.

The outsiders of the society, the unadapted like the witches and the robbers fled into the woods. As threatening animal species were eradicated, the need to protect themselves against them got unnecessary, too. A new relationship to 'nature' came up. The human settlements could allow nature in a domesticated form, in this form nature could florish even for representation. The result was the garden and landscape park. Nature became a recreational area. The bear became a mascot.

The explosive growth of cities in the 19th century, had as a result unhealthy living conditions in crowded urban neighborhoods, unbearably dangerous for all residents. The city had to be ventilated - in the literal sense. Fortuned men donated ground and sponcered parcs. Nature evolved from a former threat to a salvation from too much city. The big cities were subjected to a first greening.

Paris was a pioneer city in this. Baron Haussmann, city planing director realized a radical solution. He broke through the gloomy, much too dense medieval quarters, with wide avenues lined with four rows of trees. He got private gardens of the city palace of the aristocracy expropriated and turned into public parks. From the middle of the 19th century, Paris became a Mecca for modern urban planning. Actually an early systematic integration of nature into city.But there were also other ideas about how to solve the urban misery: others denied the territorial reality of the rapid increase in population in the cities, they had the intention to turn this back and to spread housing over a wide space. They dreamed of a rather romantic relationship between city and nature.

In their hearts, they were hostile to the city. Their supporters envisioned a quasi village side by side. The concept of Garden City by Englishman Howard, for example, proclaimed the idyl of low-rise buildings framed by gardens. Even at the time of its formulation in 1898, this was already an unrealistic solution to the settlement of the many people who flocked to the cities.

But what is a realistic view of the relationship between city and nature today? What would the city be like nature? Would there be a realistic form of the garden city today that harmoniously combines both? The earth population has grown explosively since then and will continue to grow.

The Dutch biologist Jelle Reumer, director of the Museum of Natural History in Rotterdam, occupies a surprising position. He also calls today's city a wildlife park. He considers the phenomenon of man and his relationship to ever-changing nature from a great distance that includes time and space (1).

He started his reflections by observing that birds in the city do not build their nests to raise their cubs with the materials that we naturally would need to use: with dry twigs, leaves, feathers. He observed that they use what they find in the city to build a nest: plastic, wire, polystyrene - materials that partly do their own work better. A few years ago, Sema Bekiroviç made an impressive photo report on such nests: she photographed the nests of coots in the canals of Amsterdam. Degree so you can find nests of urban swans equipped with plastic or wire-mesh crow's nests. There can be no question of repression here.

What man has created with the big city is obviously a new, adapted to him, an 'andropogenes' ecosystem. Of course, an ecosystem in which only a selection of varieties of the entire flora and fauna has established itself, varieties that can handle the structural conditions created by the people. So not the tigers and lynxes, not the oriole and the bitterns, but varieties that see rock formations in the mostly barren cities, into which they can expand their settlement area. The rock pigeons have done that, the seagulls, the crows and others.

Findings arise when you expand the field of view, when you look at the thing or the problem from a long distance and recognize the big connections. What makes the position of Jelle Reumer so exciting is the big time horizon under which he views the world as we experience it hic et nunc: It outlines a history of billions of years. What we care for today as 'nature' in our inner imagination is in fact a chain of ever-changing ecosystems in which even the rampant ecosystem 'city' may well be just an interlude in the next billion years of Earth's future becomes.

This ecosystem of the city is just as wild for the flora and fauna that have nestled here (and will re-nest under changing climatic conditions) as the wilderness was and is out of town. Some animals have already followed humans early into their homes: the dog, the house mouse, the sparrow, the cat. They have adapted. But even the newer immigrants adapt - the blackbird, which I only knew as a forest bird in my childhood, is now looking for insects and worms at the roots of the trees in the Amsterdam canals; the former shy egret hunts from the quay walls. One morning when I opened the front door in Amsterdam, there was a heron sitting on the railing, completely unmoved. A nice passerby took a snapshot.

Other varieties have specialized in our waste, as the crows and city pigeons, the daytime our edible leftovers and barely leave the nocturnal rats …. But we, as homo sapiens, coming from the savanna, have adapted to this ecosystem city so that Jelle Reumer speaks of homo sapiens becoming homo urbanus (see his essay on BCJ ‘homo urbanus – the human of our urbanized future’). Being exposed to the savannah, he says, we would not be able to survive for 10 days. In fact, research has shown that ‘the city children’s senses are dwindling’: they look worse, their ability to move and their sense of smell have decreased, even compared to children from two generations ago. Nature does not care whether the changes are man-made or a natural process, a storm, a landslide or similar. they have produced. It adapts to its inexhaustible adaptability. “Qua impact is a storm-thrown tree no less incisive than human intervention by an excavator” (Jelle Reumer, Wildlife in Rotterdam). The place devastated by our construction measures still remains a natural area, albeit in a different form. But our human intervention with the construction of cities has consequences for the living conditions not only of flora and fauna, but also of us, the human causers and beneficiaries themselves. This is what we need to investigate. To make clear what the city means as a natural area, Reumer comes up with a drastic comparison: on the banks of the river Rotte there is a colony of cormorants somewhere in the trees. These trees are completely overloaded with innumerable nests. He writes: “There is an almost apocalyptic sight …. the trees are almost completely dead and completely white with feces, which are all stuck in thick layers on them; any kind of growth at the foot of the trees has disappeared. This is what it looks like when a single species, in this case the cormorants, is dominant in an area. It fills the area with its nests and uninhibitedly pollutes the whole environment, making many other species of animals and plants no longer feel at home and disappear. “ Now read these sentences again, he writes, and replace the word ‘cormorant’ with ‘man’: “That’s the almost perfect definition of city! A packed collection of human nests, better known as buildings, with pretty little room for other varieties and mostly quite dirty. “ It is an impressive comparison. A comparison that shows us what our problem with our dense cities is: we destroy the living conditions of many varieties and, ultimately, those of ourselves. If we want to stop, not because of an alleged destruction of nature. “The city does not destroy nature. She can not be displaced. Nature is a succession of ecosystems; it is nonsensical to judge one ecosystem higher than the other “. It is only from our own, interest-driven perspective that we come to value one ecosystem higher than the other. Sub specie aeternitatis is nonsensical. It is about ourselves: to secure our own living conditions, to the living conditions for us people in the city. And there threatens the danger of destroying the livelihoods of not only other varieties, but also the destruction of the livelihoods of our own species, of us humans. But both – and that is the central insight – are related.

Climate change

Another thing added: Keyword climate change: It is daily in the media to follow – long-lasting heat periods and long-lasting heavy rain, floods, storms. Drying of vast tracts of land on a global scale and sea-level rise; thereby triggered loss of settlement areas and agriculturally usable areas; This triggered migrations of peoples, known only as a so-called refugee crisis. However, the extent of climate-induced migrations greatly exceeds that of war-caused flight movements worldwide. In summary: We are currently dealing with fundamentally changing conditions. The relatively young sciences, which deal with the biological, ecological and meteorological side of our world, sound the alarm. Fast rethinking, energetic reversal is needed. But that also means that we are facing fundamentally changed conditions for the dense city and for sustainable architecture and a sustainable urban development. The consequences of climate change are an essential cause. Once again: So it’s about the living conditions for the species homo sapiens in the city. And this question is now in a tightened form. It is by no means ‘only’ biodiversity, the destruction of the livelihoods of flora and fauna through urbanization, urban land-grabbing and agrarian monocultures. It is also about the destruction of the livelihoods of us humans themselves. However, the way out is not the nature reserve for flora and fauna and for us the back to the garden city à la Ebenezer Howard. We have to put both requirements on top of each other: we have to realize that the dense city itself has to become ‘nature’, i. to a form of nature that can secure our physical and psychological survival as a species. Thus, an old dream, an old idea has re-entered the stage: the idea of peaceful coexistence and cooperation with nature. We begin to understand our existential dependence on ‘nature’ – more precisely, our dependence on extra-human nature. We understand that we are only part of a whole, albeit a very aggressive, dominant part. Our vital breathing air must be produced by plants and trees, and these are also air purifying systems and moisture management systems – with ingenious ‘natural’ technology that works far better than our almost bumbling, albeit scientifically sound technical installations. The great rethinking is emerging: Instead of separation of city and nature of both integration: constructive coexistence in the dense and equally densely green city.

Abbildungen Helga Fassbinder, Sema Bekiroviç (2), Schreiner&Kastler (1), Buro Baustadtrat Ludwig (1)